- 前書き / Preface

- 第1章:関所とは何か / Chapter 1: What Were Checkpoints?

- 第2章:関所の起源と歴史 / Chapter 2: The Origins and History of Checkpoints

- 第3章:主要な関所の配置 / Chapter 3: Placement of Major Checkpoints

- 第4章:「入鉄砲に出女」の意味 / Chapter 4: The Meaning of “Incoming Guns and Outgoing Women”

- 第5章:通行手形の種類と取得方法 / Chapter 5: Types of Travel Permits and How to Obtain Them

- 第6章:関所の建築と構造 / Chapter 6: Architecture and Structure of Checkpoints

- 第7章:関所役人の組織と役割 / Chapter 7: Organization and Roles of Checkpoint Officials

- 第8章:検査の実際の手順 / Chapter 8: Actual Inspection Procedures

- 第9章:女性の通行と「女手形」 / Chapter 9: Women’s Passage and “Women’s Permits”

- 第10章:抜け道と密行の手口 / Chapter 10: Secret Paths and Methods of Illicit Passage

- 第11章:関所破りの罪と刑罰 / Chapter 11: The Crime of Checkpoint Violation and Punishments

- 第12章:関所町の発展 / Chapter 12: Development of Checkpoint Towns

- 第13章:関所の一日 / Chapter 13: A Day at the Checkpoint

- 第14章:季節による違い / Chapter 14: Seasonal Differences

- 第15章:特別な旅人たち / Chapter 15: Special Travelers

- 第16章:関所の廃止 / Chapter 16: Abolition of Checkpoints

- 第17章:復元された関所 / Chapter 17: Restored Checkpoints

- 第18章:関所に関する伝説と物語 / Chapter 18: Legends and Stories About Checkpoints

- 第19章:関所と参勤交代 / Chapter 19: Checkpoints and Alternate Attendance

- 第20章:関所が残した影響 / Chapter 20: The Legacy Left by Checkpoints

- 第21章:関所から学ぶ教訓 / Chapter 21: Lessons Learned from Checkpoints

- あとがき / Afterword

前書き / Preface

江戸時代、日本全国に設置された関所は、単なる検問所以上の役割を果たしていました。幕府の統治システムの要として、人々の移動を管理し、治安を維持し、時には地域経済の中心ともなりました。本ブログでは、関所の歴史、機能、日常、そして現代に残る遺産まで、21章にわたって詳しく探っていきます。

During the Edo period, checkpoints established throughout Japan served roles far beyond simple inspection stations. As a cornerstone of the shogunate’s governance system, they managed people’s movement, maintained public order, and sometimes became centers of regional economies. In this blog, we will explore in detail across 21 chapters the history, functions, daily life, and legacy that remains today of these checkpoints.

第1章:関所とは何か / Chapter 1: What Were Checkpoints?

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 関所(せきしょ)- checkpoint, barrier station

- 番所(ばんしょ)- guard station

- 取り締まり(とりしまり)- control, regulation

- 通行手形(つうこうてがた)- travel permit

関所は、江戸幕府が主要街道に設置した検問施設です。旅人や商人の通行を管理し、特に「入鉄砲に出女」と呼ばれる武器の流入と女性の江戸からの脱出を厳しく取り締まりました。全国に約50箇所設置され、幕府直轄のものと藩が管理するものがありました。

Checkpoints were inspection facilities established by the Edo shogunate on major highways. They managed the passage of travelers and merchants, strictly controlling especially what was called “incoming guns and outgoing women” – the influx of weapons and women’s escape from Edo. About 50 were established nationwide, with some under direct shogunate control and others managed by domains.

対話文 / Dialogue:

旅人:「この関所を通るには何が必要ですか?」 Traveler: “What do I need to pass through this checkpoint?”

番人:「通行手形を見せてください。お持ちでない方は通れません。」 Guard: “Please show me your travel permit. Those without one cannot pass.”

旅人:「はい、こちらです。目的地は京都です。」 Traveler: “Yes, here it is. My destination is Kyoto.”

番人:「確認しました。お通りください。道中お気をつけて。」 Guard: “Confirmed. Please proceed. Take care on your journey.”

第2章:関所の起源と歴史 / Chapter 2: The Origins and History of Checkpoints

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 古代(こだい)- ancient times

- 律令制(りつりょうせい)- ritsuryō system

- 戦国時代(せんごくじだい)- Warring States period

- 確立(かくりつ)- establishment

関所の起源は古代の律令制にまで遡ります。平安時代には主要道路に関が設けられましたが、戦国時代になると各地の大名が領国の境界に関所を設置し、通行税を徴収しました。江戸時代に入ると、徳川家康が全国統一の一環として関所制度を再編成し、幕府の統治機構として確立させました。

The origins of checkpoints trace back to the ancient ritsuryō system. During the Heian period, barriers were established on major roads, but in the Warring States period, daimyō across the land set up checkpoints at their domain boundaries to collect transit taxes. Upon entering the Edo period, Tokugawa Ieyasu reorganized the checkpoint system as part of national unification, establishing it as a governance mechanism of the shogunate.

対話文 / Dialogue:

学者:「関所はいつ頃から存在したのですか?」 Scholar: “Since when have checkpoints existed?”

役人:「古代からありましたが、今の形になったのは徳川様の時代からです。」 Official: “They existed since ancient times, but took their current form from Lord Tokugawa’s era.”

学者:「戦国時代とは違うのですね。」 Scholar: “So it differs from the Warring States period.”

役人:「はい。今は天下泰平のための制度として整備されています。」 Official: “Yes. Now it is organized as a system for peace throughout the realm.”

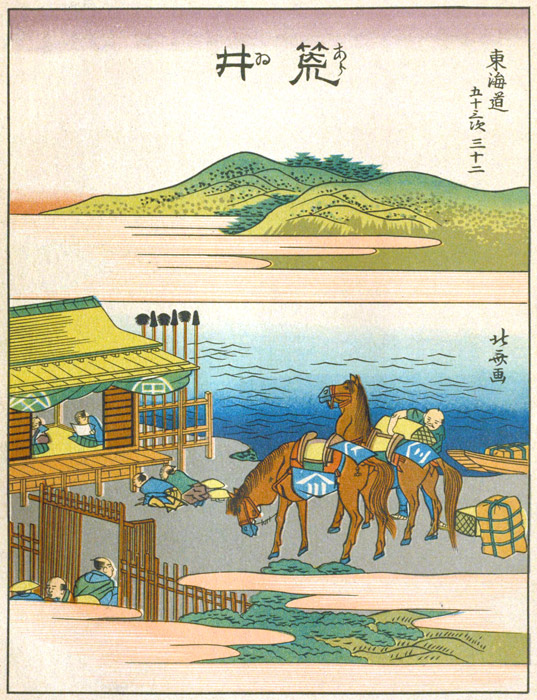

第3章:主要な関所の配置 / Chapter 3: Placement of Major Checkpoints

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 箱根(はこね)- Hakone

- 新居(あらい)- Arai

- 碓氷(うすい)- Usui

- 東海道(とうかいどう)- Tōkaidō (Eastern Sea Road)

最も重要な関所は、東海道の箱根と新居、中山道の碓氷と福島でした。これらは「四大関所」と呼ばれ、特に厳重な警備が敷かれていました。箱根関所は江戸の西の守りとして、新居関所は浜名湖を利用した水上検問も行っていました。その他、木曽路、北陸道、奥州街道などにも重要な関所が配置されていました。

The most important checkpoints were Hakone and Arai on the Tōkaidō, and Usui and Fukushima on the Nakasendō. These were called the “Four Great Checkpoints” and had particularly strict security. Hakone checkpoint served as the western defense of Edo, while Arai checkpoint also conducted waterway inspections using Lake Hamana. Additionally, important checkpoints were placed on routes such as the Kiso Road, Hokuriku Road, and Ōshū Highway.

対話文 / Dialogue:

商人:「箱根の関所は厳しいと聞きましたが本当ですか?」 Merchant: “I heard Hakone checkpoint is strict, is that true?”

案内人:「ええ、四大関所の一つですから。特に女性の取り締まりが厳重です。」 Guide: “Yes, it’s one of the Four Great Checkpoints. Women’s inspection is particularly stringent.”

商人:「新居も同じくらい厳しいのですか?」 Merchant: “Is Arai equally strict?”

案内人:「そうですね。あちらは湖の検問もありますから。」 Guide: “Indeed. There are also lake inspections there.”

第4章:「入鉄砲に出女」の意味 / Chapter 4: The Meaning of “Incoming Guns and Outgoing Women”

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 鉄砲(てっぽう)- gun, firearm

- 人質(ひとじち)- hostage

- 謀反(むほん)- rebellion, treason

- 大名(だいみょう)- feudal lord

「入鉄砲に出女」は関所取り締まりの基本方針でした。「入鉄砲」は江戸への武器持ち込みを防ぎ、謀反を未然に防ぐためです。「出女」は江戸に住む大名の妻子が無断で国元に帰るのを防ぎました。彼女たちは事実上の人質であり、大名の謀反を抑止する役割を果たしていました。この二つの取り締まりが関所の最重要任務でした。

“Incoming guns and outgoing women” was the basic policy of checkpoint control. “Incoming guns” prevented weapons from being brought into Edo to forestall rebellion. “Outgoing women” prevented daimyō wives and children living in Edo from returning to their home domains without permission. They were effectively hostages, serving to deter daimyō rebellion. These two controls were the checkpoints’ most important duties.

対話文 / Dialogue:

若者:「なぜ女性の通行が厳しく取り締まられるのですか?」 Youth: “Why is women’s passage so strictly controlled?”

老人:「大名の奥方様が人質だからじゃ。勝手に江戸を出られては困る。」 Elder: “Because daimyō wives are hostages. It would be troublesome if they left Edo freely.”

若者:「鉄砲はどうなのですか?」 Youth: “What about guns?”

老人:「江戸に武器が入れば謀反の恐れがある。だから厳しいのじゃ。」 Elder: “If weapons enter Edo, there’s fear of rebellion. That’s why it’s strict.

第5章:通行手形の種類と取得方法 / Chapter 5: Types of Travel Permits and How to Obtain Them

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 往来手形(おうらいてがた)- travel pass

- 関所手形(せきしょてがた)- checkpoint permit

- 寺請証文(てらうけしょうもん)- temple certification

- 五人組(ごにんぐみ)- five-household group

旅をするには通行手形が必要でした。一般的な往来手形は寺や村役人から発行され、身元を証明しました。女性が関所を通るには特別な「女手形」が必要で、身分や容貌が詳しく記載されました。商人には商用手形、武士には藩からの公用手形が発行されました。手形を偽造すると厳罰に処せられました。

Travel permits were required for journeys. General travel passes were issued by temples or village officials and certified one’s identity. Women needed special “women’s permits” to pass checkpoints, which detailed their status and appearance. Merchants received commercial permits, and samurai received official permits from their domains. Forging permits was severely punished.

対話文 / Dialogue:

農民:「旅に出たいのですが、手形はどこで手に入りますか?」 Farmer: “I want to travel, but where can I get a permit?”

村役人:「村の寺で寺請証文をもらい、それを持って私のところへ来なさい。」 Village official: “Get temple certification from the village temple, then bring it to me.”

農民:「女房も連れて行きたいのですが。」 Farmer: “I want to take my wife along.”

村役人:「女性には特別な手形が必要だ。容貌書きも必要になるぞ。」 Village official: “Women need special permits. A physical description will also be required.”

第6章:関所の建築と構造 / Chapter 6: Architecture and Structure of Checkpoints

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 門(もん)- gate

- 番小屋(ばんごや)- guard hut

- 遠見番所(とおみばんしょ)- watchtower

- 柵(さく)- fence, palisade

関所の建築は防御と監視を重視した設計でした。入口には頑丈な門があり、その両側に番小屋が配置されました。見張り台からは周辺を監視し、不正な通行を防ぎました。建物は質素ながら、権威を示す造りとなっており、旅人に幕府の力を印象づけました。箱根関所では、芦ノ湖畔に面して建ち、水上からの迂回も防いでいました。

Checkpoint architecture emphasized defense and surveillance. Sturdy gates stood at entrances, with guard huts positioned on both sides. Watchtowers surveyed the surroundings to prevent illegal passage. Though austere, buildings were constructed to display authority, impressing upon travelers the shogunate’s power. At Hakone checkpoint, structures faced Lake Ashi to prevent detours by water.

対話文 / Dialogue:

大工:「この関所の設計は誰が考えたのですか?」 Carpenter: “Who designed this checkpoint?”

役人:「幕府の指示に基づいて建てられた。防御が第一だ。」 Official: “It was built according to shogunate instructions. Defense is paramount.”

大工:「見張り台が高いですね。」 Carpenter: “The watchtower is quite tall.”

役人:「遠くまで見渡せるようにな。抜け道を使う者を見逃さない。」 Official: “So we can see far into the distance. We won’t miss anyone using secret paths.”

第7章:関所役人の組織と役割 / Chapter 7: Organization and Roles of Checkpoint Officials

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 番頭(ばんがしら)- head guard

- 番士(ばんし)- guard samurai

- 足軽(あしがる)- foot soldier

- 改め女(あらためおんな)- female inspector

関所には厳格な組織がありました。最高責任者は番頭で、複数の番士が実務を担当しました。足軽は門の警備や雑務を行いました。特筆すべきは「改め女」で、女性旅人の身体検査を行う専門職でした。彼女たちは手形と本人の照合、変装の見破りなど、重要な役割を果たしました。

Checkpoints had strict organizations. The head guard was the top official, with multiple guard samurai handling practical affairs. Foot soldiers guarded gates and performed miscellaneous tasks. Notably, “female inspectors” were specialists who conducted physical examinations of female travelers. They performed important roles such as matching permits with individuals and detecting disguises.

対話文 / Dialogue:

新人:「改め女とはどんな仕事ですか?」 Newcomer: “What kind of work do female inspectors do?”

先輩:「女性の旅人を調べる。手形と顔が合っているか、男装していないかなど。」 Senior: “They examine female travelers. Whether face matches permit, if disguised as men, etc.”

新人:「難しそうですね。」 Newcomer: “Sounds difficult.”

先輩:「経験が必要だ。髪型や歩き方で見抜くこともある。」 Senior: “Experience is necessary. Sometimes detected through hairstyle or gait.”

第8章:検査の実際の手順 / Chapter 8: Actual Inspection Procedures

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 尋問(じんもん)- interrogation, questioning

- 照合(しょうごう)- verification, cross-checking

- 身体検査(しんたいけんさ)- body search

- 荷物改め(にもとあらため)- baggage inspection

検査は段階的に行われました。まず手形の提示と目的地の確認、次に手形記載内容と本人の照合が行われました。疑わしい場合は詳しい尋問が続き、女性の場合は改め女による身体検査も実施されました。荷物も開けて調べられ、禁制品がないか確認されました。通常、検査は数分で終わりましたが、混雑時は数時間待つこともありました。

Inspections were conducted in stages. First came presentation of permits and confirmation of destination, then verification of permit contents with the individual. In suspicious cases, detailed interrogation followed, and for women, body searches by female inspectors were conducted. Baggage was also opened and examined to confirm no prohibited items. Normally inspections finished in minutes, but during congestion could require waiting several hours.

対話文 / Dialogue:

番人:「手形を拝見します。どちらへ?」 Guard: “I’ll examine your permit. Where are you headed?”

商人:「大坂へ商いに参ります。」 Merchant: “I’m going to Osaka for business.”

番人:「荷物を開けてください。何を運んでいますか?」 Guard: “Please open your baggage. What are you carrying?”

商人:「反物と茶葉でございます。どうぞご確認を。」 Merchant: “Fabric and tea leaves. Please verify.”

第9章:女性の通行と「女手形」 / Chapter 9: Women’s Passage and “Women’s Permits”

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 容貌書き(ようぼうがき)- physical description

- 人相(にんそう)- facial features

- 年齢(ねんれい)- age

- 背丈(せたけ)- height

女性が関所を通過するには、詳細な「女手形」が必要でした。手形には年齢、背丈、顔の特徴、髪型、同行者などが詳しく記載されました。改め女は手形と実際の容貌を慎重に照合し、少しでも疑問があれば通行を許可しませんでした。これは大名の妻女が変装して逃亡するのを防ぐための厳格な措置でした。

For women to pass checkpoints, detailed “women’s permits” were required. Permits recorded in detail age, height, facial features, hairstyle, companions, and more. Female inspectors carefully verified permits against actual appearance, and if any doubt existed, would not permit passage. This was a strict measure to prevent daimyō wives from escaping in disguise.

対話文 / Dialogue:

改め女:「手形と顔を確認させていただきます。」 Female inspector: “I will verify your permit and face.”

女性旅人:「はい、どうぞ。伊勢参りに行く者です。」 Female traveler: “Yes, please do. I’m going on pilgrimage to Ise.”

改め女:「年は二十五とありますが、間違いありませんね?」 Female inspector: “It says age twenty-five, is that correct?”

女性旅人:「はい。生まれは寛政九年でございます。」 Female traveler: “Yes. I was born in Kansei 9.”

第10章:抜け道と密行の手口 / Chapter 10: Secret Paths and Methods of Illicit Passage

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 抜け道(ぬけみち)- secret path, bypass

- 山越え(やまごえ)- mountain crossing

- 密行(みっこう)- illicit travel

- 人足(にんそく)- porter, guide

関所を避けるための抜け道も存在しました。山道を使った迂回路、船での湖や川の横断など、様々な方法が試みられました。地元の人足が案内役となることもありましたが、発覚すれば厳罰でした。箱根では芦ノ湖を小舟で渡る者、碓氷では険しい山道を越える者がいました。しかし、幕府は巡回を強化し、抜け道の使用を厳しく取り締まりました。

Secret paths to avoid checkpoints also existed. Various methods were attempted: detour routes using mountain trails, crossing lakes and rivers by boat, and more. Local porters sometimes served as guides, but if discovered faced severe punishment. At Hakone some crossed Lake Ashi in small boats, at Usui some traversed steep mountain paths. However, the shogunate strengthened patrols and strictly controlled use of secret paths.

対話文 / Dialogue:

逃亡者:「山越えの道を知っているか?」 Fugitive: “Do you know the mountain crossing route?”

人足:「知っているが、危険だぞ。見つかれば打ち首だ。」 Porter: “I know it, but it’s dangerous. If found, you’ll be beheaded.”

逃亡者:「それでもいい。案内してくれ。」 Fugitive: “That’s fine. Guide me.”

人足:「夜になったら出発する。荷物は最小限にしろ。」 Porter: “We leave when night falls. Keep baggage to a minimum.”

第11章:関所破りの罪と刑罰 / Chapter 11: The Crime of Checkpoint Violation and Punishments

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 打ち首(うちくび)- beheading

- 磔(はりつけ)- crucifixion

- 獄門(ごくもん)- public display of severed head

- 遠島(えんとう)- exile to remote island

関所破りは重罪でした。無許可で関所を通過した者、抜け道を使った者、手形を偽造した者は厳罰に処せられました。最も重い刑は打ち首や磔で、遺体は見せしめとして晒されました。女性でも例外はなく、大名の妻女が関所破りを企てれば、その大名も処罰されました。案内した者も同罪とされ、連座制が適用されました。

Checkpoint violation was a serious crime. Those who passed checkpoints without permission, used secret paths, or forged permits were severely punished. The heaviest punishments were beheading or crucifixion, with bodies displayed as warnings. Even women received no exception, and if a daimyō’s wife attempted checkpoint violation, the daimyō himself was also punished. Guides were considered equally guilty, with collective responsibility applied.

対話文 / Dialogue:

役人:「そなた、関所を破った罪で捕らえた。」 Official: “You are arrested for the crime of checkpoint violation.”

犯人:「お許しを!妻が病で、急いで帰らねば…」 Criminal: “Mercy! My wife is ill, I must hurry home…”

役人:「理由は聞かぬ。法は法だ。覚悟せよ。」 Official: “I hear no reasons. Law is law. Prepare yourself.”

犯人:「せめて家族には知らせを…」 Criminal: “At least let my family know…”

第12章:関所町の発展 / Chapter 12: Development of Checkpoint Towns

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 宿場町(しゅくばまち)- post town

- 旅籠(はたご)- inn

- 茶屋(ちゃや)- tea house

- 商人(しょうにん)- merchant

関所の周辺には宿場町が発達しました。旅人は関所の開門時間に合わせて到着する必要があり、前泊や後泊のための宿が必要でした。旅籠、茶屋、土産物屋、馬宿などが軒を連ね、地域経済の中心となりました。箱根の関所町は特に栄え、温泉宿も多く建ちました。関所が地域の雇用と経済を支えていました。

Post towns developed around checkpoints. Travelers needed to arrive according to checkpoint opening hours, requiring lodging for pre- or post-passage stays. Inns, tea houses, souvenir shops, horse stables and more lined the streets, becoming regional economic centers. Hakone’s checkpoint town particularly prospered, with many hot spring inns built. Checkpoints supported regional employment and economy.

対話文 / Dialogue:

旅籠の主人:「今日は関所が混んでいるから、泊まっていきなさい。」 Inn master: “The checkpoint is crowded today, so stay the night.”

旅人:「明日の朝なら空いていますか?」 Traveler: “Will it be less crowded tomorrow morning?”

主人:「朝一番なら比較的早く通れるでしょう。」 Master: “If you go first thing in the morning, you can pass relatively quickly.”

旅人:「では一泊お願いします。風呂はありますか?」 Traveler: “Then I’ll stay one night. Do you have a bath?”

第13章:関所の一日 / Chapter 13: A Day at the Checkpoint

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 夜明け(よあけ)- dawn

- 開門(かいもん)- gate opening

- 閉門(へいもん)- gate closing

- 交代(こうたい)- shift change

関所は日の出とともに開門し、日没で閉門しました。夜間は誰も通行できず、緊急の場合でも例外はありませんでした。朝は旅人が列を作り、番人は一人ずつ丁寧に検査しました。昼過ぎが最も混雑し、夕方になると慌てて駆け込む旅人もいました。役人は交代制で勤務し、常に警戒を怠りませんでした。

Checkpoints opened at sunrise and closed at sunset. No one could pass at night, with no exceptions even in emergencies. Mornings saw travelers form lines, with guards carefully inspecting each person. Mid-afternoon was most congested, and toward evening some travelers rushed in. Officials worked in shifts, never letting down their guard.

対話文 / Dialogue:

番人:「もうすぐ閉門の時刻だ。急ぎなさい。」 Guard: “Gate closing time is soon. Hurry.”

旅人:「すみません、道に迷ってしまいまして。」 Traveler: “Apologies, I got lost on the road.”

番人:「日が暮れたら通せない。急いで手形を出しなさい。」 Guard: “Can’t let you pass after sunset. Quickly show your permit.”

旅人:「はい、こちらです。どうか通してください。」 Traveler: “Yes, here it is. Please let me through.”

第14章:季節による違い / Chapter 14: Seasonal Differences

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 雪(ゆき)- snow

- 洪水(こうずい)- flood

- 参詣(さんけい)- pilgrimage

- 農閑期(のうかんき)- off-season for farming

季節により関所の様子は大きく変わりました。春と秋は伊勢参りや善光寺参りの旅人で混雑しました。夏は暑さで旅人が減りましたが、農閑期の冬は意外に多くの旅人がいました。雪や洪水で街道が通行困難になることもあり、関所も一時閉鎖されることがありました。天候による通行制限も厳格に守られました。

Checkpoint conditions changed greatly with seasons. Spring and autumn were crowded with pilgrims to Ise and Zenkōji. Summer saw fewer travelers due to heat, but winter’s farming off-season surprisingly brought many travelers. Snow and floods sometimes made highways impassable, and checkpoints were temporarily closed. Weather-based passage restrictions were strictly observed.

対話文 / Dialogue:

旅人:「雪で道が通れないと聞きましたが。」 Traveler: “I heard the road is impassable due to snow.”

番人:「今日は閉鎖だ。雪が溶けるまで待ちなさい。」 Guard: “We’re closed today. Wait until the snow melts.”

旅人:「どのくらいかかりますか?」 Traveler: “How long will that take?”

番人:「二、三日といったところか。宿に泊まりなさい。」 Guard: “Two or three days perhaps. Stay at an inn.”

第15章:特別な旅人たち / Chapter 15: Special Travelers

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 公家(くげ)- court noble

- 僧侶(そうりょ)- Buddhist priest

- 朝鮮通信使(ちょうせんつうしんし)- Korean envoys

- 琉球使節(りゅうきゅうしせつ)- Ryukyuan envoys

関所には様々な身分の旅人が訪れました。公家や高位の僧侶には特別な敬意が払われ、検査も簡略化されました。朝鮮通信使や琉球使節といった外国使節団は、事前に通知があり、盛大に迎えられました。しかし、どんな身分であろうと、基本的な手形の確認は省略されませんでした。幕府の権威はすべての者に平等に及びました。

Checkpoints received travelers of various ranks. Court nobles and high-ranking priests received special respect with simplified inspections. Foreign envoys like Korean and Ryukyuan missions had advance notice and were received grandly. However, regardless of status, basic permit verification was never omitted. The shogunate’s authority extended equally to all.

対話文 / Dialogue:

番人:「明日、朝鮮通信使がお通りになる。準備を整えよ。」 Guard: “Korean envoys pass through tomorrow. Make preparations.”

部下:「どのような対応をすればよいですか?」 Subordinate: “What response should we make?”

番人:「最大限の敬意を払うが、手形の確認は必ず行え。」 Guard: “Show maximum respect, but definitely verify permits.”

部下:「承知しました。清掃も念入りにいたします。」 Subordinate: “Understood. We’ll also clean thoroughly.”

第16章:関所の廃止 / Chapter 16: Abolition of Checkpoints

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 明治維新(めいじいしん)- Meiji Restoration

- 廃止(はいし)- abolition

- 自由通行(じゆうつうこう)- free passage

- 近代化(きんだいか)- modernization

明治維新により、1869年(明治2年)に全国の関所が廃止されました。新政府は人々の移動の自由を重視し、封建的な制度の象徴である関所を撤廃しました。これにより、誰でも手形なしで自由に旅ができるようになりました。関所の廃止は、日本の近代化と中央集権化の重要な一歩でした。約260年続いた関所制度は、こうして歴史の幕を閉じました。

With the Meiji Restoration, all checkpoints nationwide were abolished in 1869 (Meiji 2). The new government valued freedom of movement and eliminated checkpoints as symbols of the feudal system. This enabled anyone to travel freely without permits. Checkpoint abolition was an important step in Japan’s modernization and centralization. Thus the checkpoint system that had lasted about 260 years closed its historical curtain.

対話文 / Dialogue:

旅人:「関所が無くなったと聞きましたが本当ですか?」 Traveler: “I heard checkpoints are gone, is it true?”

元番人:「ああ、新政府の命令で廃止された。時代が変わったのだ。」 Former guard: “Yes, abolished by order of the new government. Times have changed.”

旅人:「これからは手形なしで旅ができるのですね。」 Traveler: “So we can travel without permits now.”

元番人:「そうだ。良い時代になるといいがな。」 Former guard: “That’s right. I hope it will be a good era.”

第17章:復元された関所 / Chapter 17: Restored Checkpoints

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 復元(ふくげん)- restoration, reconstruction

- 史跡(しせき)- historic site

- 観光地(かんこうち)- tourist destination

- 文化財(ぶんかざい)- cultural property

現代では、いくつかの関所が復元され、観光地となっています。箱根関所は2007年に江戸時代の姿に復元され、当時の建物や設備を見学できます。福島関所、木曽福島関所なども部分的に復元されています。これらの史跡は、江戸時代の交通制度を学ぶ貴重な教育の場となっており、多くの観光客が訪れています。

In modern times, several checkpoints have been restored and become tourist destinations. Hakone checkpoint was restored to its Edo period appearance in 2007, allowing visitors to tour period buildings and facilities. Fukushima checkpoint, Kiso-Fukushima checkpoint and others are also partially restored. These historic sites serve as valuable educational venues for learning about Edo period transportation systems, attracting many tourists.

対話文 / Dialogue:

観光客:「この建物は本物ですか?」 Tourist: “Is this building authentic?”

ガイド:「復元されたものですが、当時の設計図を基に忠実に再現しています。」 Guide: “It’s restored, but faithfully recreated based on original blueprints.”

観光客:「中に入れますか?」 Tourist: “Can we go inside?”

ガイド:「はい、番小屋や牢屋も見学できます。当時の雰囲気を感じてください。」 Guide: “Yes, you can tour the guard hut and jail. Please feel the atmosphere of the time.”

第18章:関所に関する伝説と物語 / Chapter 18: Legends and Stories About Checkpoints

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 伝説(でんせつ)- legend

- 歌舞伎(かぶき)- kabuki theater

- 浮世絵(うきよえ)- ukiyo-e woodblock prints

- 逸話(いつわ)- anecdote

関所を舞台にした多くの伝説や物語が伝わっています。変装して関所を破ろうとする女性、厳格な番人と旅人の知恵比べ、悲恋の物語など、様々な話があります。歌舞伎や浮世絵にも関所はしばしば登場し、庶民の想像力を刺激しました。これらの物語は、関所が単なる検問所ではなく、ドラマの舞台でもあったことを示しています。

Many legends and stories set at checkpoints have been passed down. Various tales exist: women attempting to breach checkpoints in disguise, contests of wit between strict guards and travelers, tragic love stories, and more. Checkpoints frequently appeared in kabuki and ukiyo-e, stimulating common people’s imagination. These stories show checkpoints were not mere inspection stations but also stages for drama.

対話文 / Dialogue:

語り部:「昔、ある女が男装して関所を破ろうとした話をご存知か?」 Storyteller: “Do you know the tale of a woman who tried to breach a checkpoint disguised as a man?”

子供:「どうなったのですか?」 Child: “What happened?”

語り部:「改め女に見破られてな。だが、その訳を聞いた番人が涙を流したという。」 Storyteller: “She was discovered by a female inspector. But hearing her reason, the guard is said to have shed tears.”

子供:「許されたのですか?」 Child: “Was she pardoned?”

第19章:関所と参勤交代 / Chapter 19: Checkpoints and Alternate Attendance

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 参勤交代(さんきんこうたい)- alternate attendance system

- 大名行列(だいみょうぎょうれつ)- daimyō procession

- 供回り(ともまわり)- retinue, attendants

- 格式(かくしき)- formality, protocol

参勤交代で江戸と国元を往復する大名にとって、関所は避けて通れない場所でした。大名行列が関所を通過する際は、特別な手続きが必要で、人数や荷物の確認が厳密に行われました。行列の格式は大名の威信を示すものであり、関所での対応も身分に応じて異なりました。関所は参勤交代制度を支える重要な装置の一つでした。

For daimyō traveling between Edo and their domains in alternate attendance, checkpoints were unavoidable. When daimyō processions passed through checkpoints, special procedures were required, with strict verification of numbers and baggage. Procession formality demonstrated daimyō prestige, and checkpoint treatment varied by status. Checkpoints were one important device supporting the alternate attendance system.

対話文 / Dialogue:

家老:「殿の行列が明日、関所を通ります。準備を。」 Chief retainer: “The lord’s procession passes the checkpoint tomorrow. Make preparations.”

番頭:「承知しております。特別な配慮をいたします。」 Head guard: “I understand. We will make special accommodations.”

家老:「しかし、手形の確認は省かないように。」 Chief retainer: “However, do not omit permit verification.”

番頭:「無論です。格式は守りますが、法は守ります。」 Head guard: “Of course. We’ll maintain formality but observe the law.”

第20章:関所が残した影響 / Chapter 20: The Legacy Left by Checkpoints

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 地名(ちめい)- place name

- 習慣(しゅうかん)- custom, habit

- 方言(ほうげん)- dialect

- 文化(ぶんか)- culture

関所は廃止されましたが、その影響は現代にも残っています。「関所」という地名、関所町として栄えた町の文化、関所にまつわる方言や慣用句などです。「関所破り」という言葉は、今でもルールを破る行為を指して使われます。また、関所があった場所の多くは交通の要所として今も重要な役割を果たしています。

Though checkpoints were abolished, their influence remains today. Place names containing “sekisho,” the culture of towns that prospered as checkpoint towns, dialects and idioms related to checkpoints, and more. The term “sekisho-yaburi” (checkpoint violation) is still used to refer to rule-breaking. Additionally, many former checkpoint locations still serve important roles as transportation hubs.

対話文 / Dialogue:

教師:「この町に『関所町』という地名が残っているのはなぜか分かりますか?」 Teacher: “Do you know why this town retains the place name ‘Sekishomachi’?”

生徒:「昔、関所があったからですか?」 Student: “Because there was a checkpoint long ago?”

教師:「その通り。歴史が地名に残っているのです。」 Teacher: “That’s right. History remains in place names.”

生徒:「他にも関所の名残はありますか?」 Student: “Are there other remnants of checkpoints?”

第21章:関所から学ぶ教訓 / Chapter 21: Lessons Learned from Checkpoints

語句メモ / Vocabulary Notes:

- 統治(とうち)- governance, rule

- 管理(かんり)- management, control

- 自由(じゆう)- freedom

- バランス(balance)- balance

関所制度は、統治と自由のバランスについて考えさせます。厳格な管理は治安を維持しましたが、人々の自由を制限しました。現代社会でも、セキュリティと自由のバランスは重要な課題です。関所の歴史は、権力の行使、監視社会の在り方、そして個人の権利について、私たちに多くのことを教えてくれます。過去を学ぶことで、より良い未来を築けるのです。

The checkpoint system makes us consider the balance between governance and freedom. Strict management maintained public order but restricted people’s freedom. Even in modern society, the balance between security and freedom remains an important issue. Checkpoint history teaches us much about the exercise of power, the nature of surveillance society, and individual rights. By learning from the past, we can build a better future.

対話文 / Dialogue:

学生:「関所は必要悪だったのでしょうか?」 Student: “Were checkpoints a necessary evil?”

教授:「当時の人々にとっては、平和を保つための制度でした。」 Professor: “For people of the time, they were a system for maintaining peace.”

学生:「でも、自由は制限されていましたね。」 Student: “But freedom was restricted.”

教授:「そうです。どんな時代も、秩序と自由のバランスが問われます。」 Professor: “Indeed. Every era grapples with balancing order and freedom.”

あとがき / Afterword

江戸時代の関所について、21章にわたってご紹介してきました。関所は単なる検問所ではなく、幕府の統治システムの重要な一部であり、地域社会の中心でもありました。厳格な規則と処罰、同時に発展した宿場町の賑わい、そして多くの人間ドラマが交差する場所でした。

現代に生きる私たちにとって、関所の歴史は遠い過去の出来事のように思えるかもしれません。しかし、セキュリティと自由、管理と権利というテーマは、今も変わらず重要です。関所という制度を通じて、私たちは江戸時代の社会を理解し、同時に現代社会についても考えることができます。

復元された関所を訪れる機会があれば、ぜひ足を運んでみてください。そこには、先人たちの知恵と工夫、そして生きた歴史が息づいています。

Across 21 chapters, we have explored checkpoints of the Edo period. Checkpoints were not mere inspection stations but important parts of the shogunate’s governance system and centers of regional communities. They were places where strict rules and punishments, the bustle of thriving post towns, and many human dramas intersected.

For us living in modern times, checkpoint history may seem like distant past events. However, themes of security and freedom, management and rights remain just as important today. Through the institution of checkpoints, we can understand Edo period society while also reflecting on contemporary society.

If you have the opportunity to visit a restored checkpoint, please do. There you will find the wisdom and ingenuity of our predecessors, and living history breathing still.

楽しく英語を学ぶならこちらから→ニュースで身につく、世界の視点と英語力。

The Japan Times Alpha

コメント